This summer marks the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a milestone that has turned Washington, D.C. into the center of a yearlong national celebration. The nation’s capital will host state-fair–style festivities, special museum exhibitions, the DC JazzFest, military commemorations, and a sweeping Fourth of July fireworks display over the National Mall. Millions of visitors will gather to celebrate the ideals of freedom and democracy – many of them looking toward one of the most recognizable buildings in the country: the U.S. Capitol.

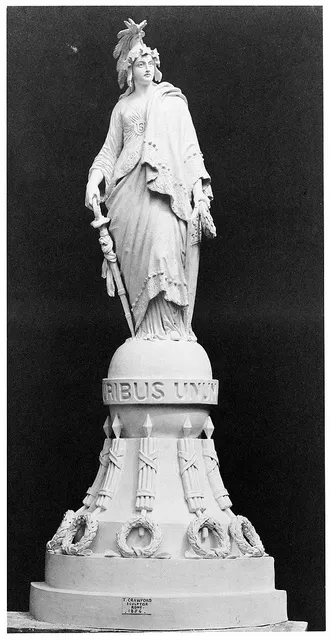

Rising above the Capitol dome, a statue will quietly watch over these celebrations, just as she has since 1863. She stands 19½ feet tall, weighs 15,000 pounds, and is cast in bronze. Known as Freedom, she wears a crested military helmet and holds a sheathed sword in her right hand, while a laurel wreath and shield rest in her left. For more than 160 years, she has presided over the National Mall as a symbol of the nation itself.

Yet despite her commanding presence and powerful symbolism, the Statue of Freedom is often overlooked, along with the remarkable story of how she was made. Even less known is the man whose skill and ingenuity were crucial to her creation: Philip Reed, an enslaved ironworker whose expertise helped bring Freedom into being. His contribution, long unrecognized, is inseparable from the monument that has come to embody American ideals.

Freedom’s Design

The iconic silhouette of the U.S. Capitol is the result of a sweeping expansion undertaken in the 1850s, as the growing nation required space for an increasing number of states and representatives. This ambitious renovation was added to the Capitol’s east and west wings and replaced the original wooden dome with the massive cast-iron structure we recognize today. From the outset, architect of this Capitol renovation Thomas U. Walter envisioned a monumental statue crowning the new dome, a design formally authorized by Congress in 1855.

Early designs for the statue, developed by both Walter and sculptor Thomas Crawford, depicted the figure wearing a liberty cap. Often shown as a soft, conical red cap, the liberty cap traces its origins to ancient Rome, where it was worn by formerly enslaved people to symbolize emancipation. By the 18th century, it had become a powerful emblem of freedom and resistance, adopted by both the American and French Revolutions.

That symbolism proved controversial. When a preliminary model of Crawford’s statue—Freedom wearing the liberty cap—was submitted to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who oversaw construction of the Capitol, it was swiftly rejected. Davis, who would later become president of the Confederate States of America, objected to the cap’s association with formerly enslaved people. He argued that “its history renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free and should not be enslaved.” Instead, Davis proposed replacing the cap with a helmet encircled by stars.

In response, Crawford redesigned the figure with a crested Roman-style helmet, retaining classical military imagery while stripping away the explicit symbol of emancipation. This revised design was approved by Davis in April 1856, and Crawford proceeded to execute the full-size clay model that would ultimately become the Statue of Freedom.

The irony is striking: a statue deliberately redesigned to remove symbols of emancipation would ultimately owe its very existence to Philip Reed, an enslaved ironworker whose skill and ingenuity were essential to casting Freedom—a work he was able to complete after gaining his own emancipation.

Philip Reed

Philip Reed (born Reid, later changing the spelling of his surname to Reed after emancipation) was born into slavery in Charleston, South Carolina, around 1820. Charleston was a major center of skilled craft labor in the antebellum South, where enslaved artisans were commonly trained and hired out for highly specialized work.

As a young man, Reed was purchased by Clark Mills, a self-taught sculptor who recognized Reed’s aptitude for metalwork and casting. In a later petition, Mills wrote that he had purchased Reed “many years ago when he was quite a youth… because of his evident talent for the business in which your petitioner was engaged,” paying $1,200 for him—a substantial sum that reflected Reed’s exceptional skill rather than his age.

During this period, Charleston had more slave-owning craftsmen and a higher concentration of enslaved skilled workers than any other city in the United States. Within this environment, artisans like Philip Reed developed expertise that would prove indispensable to some of the nation’s most ambitious artistic and architectural projects, even as their labor went uncredited and their freedom denied.

Little documentation survives about Philip Reed’s life in South Carolina, but it is likely that he lived and worked at Clark Mills’s residence and studio at 51 Broad Street in Charleston, where Mills trained him in sculpting, plasterwork, and the practical mechanics of large-scale casting.

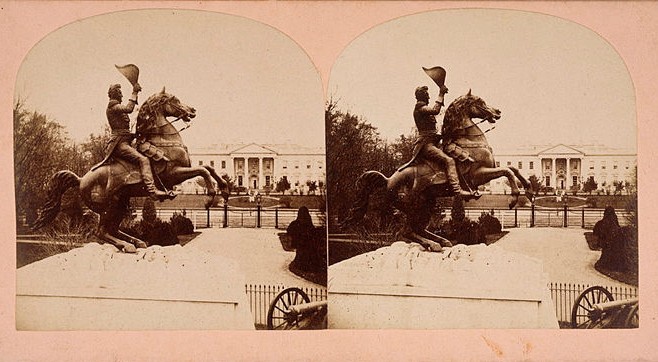

In the late 1840s, Mills relocated to Washington, D.C., after winning the competition to create an equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson for Lafayette Square. Reed was brought with him—an indication of how essential his skills had already become to Mills’s work. In Washington, Mills increasingly relied on Reed’s expertise in ironworking and foundry practice, later describing him as

“smart in mind, a good workman in a foundry.”

Working largely through experimentation rather than formal training, Mills, Reed, and a small team of laborers achieved a remarkable first: the successful casting of the first bronze statue ever produced in the United States. Completed in 1852, the Equestrian Statue of Andrew Jackson was also technically groundbreaking, balancing entirely on the horse’s hind legs—an unprecedented engineering feat at the time. That such an accomplishment was achieved without academic training makes the success even more extraordinary.

The triumph of the Jackson statue brought Mills national recognition and led to additional high-profile commissions. Among them was the casting of Thomas Crawford’s Statue of Freedom for the summit of the Capitol’s newly constructed dome. To meet the scale of this undertaking, Mills purchased land along Bladensburg Road in Maryland, where he built a dedicated studio and foundry. It was there, in this purpose-built space, that the Statue of Freedom would be cast—with Philip Reed once again playing a crucial role.

(National Archives)

In June 1860, the casting of the Statue of Freedom began. The process started by disassembling the plaster model into its five main sections so it could be transported from the Capitol to Mills’s Maryland foundry. The model had been shipped from Rome in five pieces, and an Italian sculptor was hired to assemble it. But when it came time to move the statue, no one knew how to separate the sections—and the Italian sculptor refused to help without a pay raise.

Philip Reed, however, rose to the challenge. Using his ingenuity, he devised a method involving a pulley and tackle to lift the ring atop the model, revealing the seams between the sections. Thanks to his plan, the plaster statue was successfully disassembled and transported to the foundry. The New York Tribune described the scene on December 10, 1863:

“The black master-builder lifted the ponderous uncouth masses, and bolted them together, joint by joint, piece by piece, till they blended into the majestic ‘Freedom.’”

While Reed is arguably the most famous of the enslaved workers on the Capitol construction, he was far from the only one. Roughly half of the workforce was composed of enslaved laborers and involved in nearly every stage of construction. Reed, however, was the only known enslaved person to work directly on the Statue of Freedom itself.

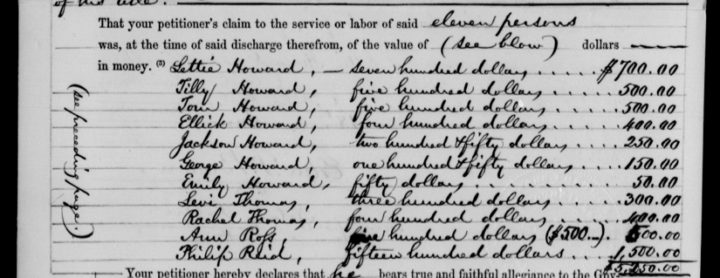

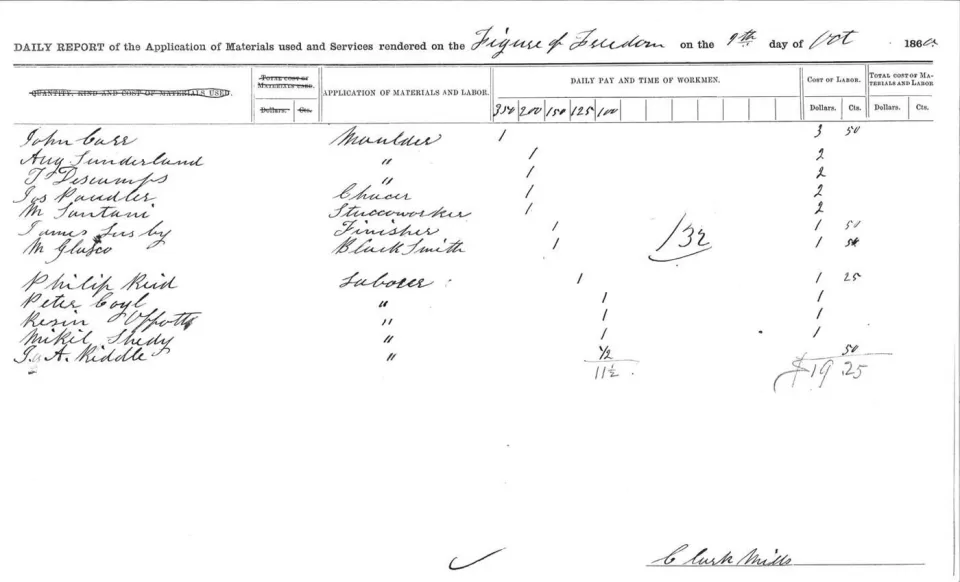

He was paid $1.25 per day for maintaining the fires beneath the casts—a rate slightly higher than other laborers, who earned $1 per day—but Mills claimed his wages for the week, allowing Reed to keep only what he earned on Sundays. Between July 1, 1860, and May 16, 1861, Reed worked almost every week without a break, earning $41.25 for 33 Sundays. He signed his name with an X, and no known images of him survive.

(The National Archives and Records Administration)

(The National Archives and Records Administration)

On April 16, 1862, slavery was abolished in Washington, D.C. Under the DC Compensated Emancipation Act, Clark Mills petitioned for payment from the federal government and freed Reed along with ten other enslaved people in his household. Reed was forty-two years old. Just over a year later, on December 2, 1863, the Statue of Freedom was unveiled atop the Capitol Dome—a testament to Reed’s skill and a poignant symbol of the freedom he could finally claim for himself.

After emancipation, Philip Reed remained in Washington, D.C., establishing a successful career as a plasterer, and was “highly esteemed by all who know him.” (S.D. Wyeth, The Federal City (1865))

Reflecting on the profound irony, a correspondent for the New York Tribune observed in 1863:

“Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom for America?”

Today, Reed’s work atop the Capitol Dome stands as a symbol of freedom realized not just in bronze, but through the skill, determination, and courage of the man who made it possible.

Sources & Further Reading

Black Men Built the Capitol — Goucher College profile referencing Jesse Holland’s work on the contributions of Black laborers. Black Men Built the Capitol – Goucher College

Philip Reid and the Statue of Freedom — Architect of the Capitol blog article on Reid’s work and the Capitol’s construction. Philip Reid and the Statue of Freedom – AOC Blog

Philip Reid (1820–1892) — BlackPast.org entry on Reid’s life and role in casting the Statue of Freedom. Philip Reid (1820–1892) – BlackPast.org

Philip Reed — White House Historical Association article detailing Reid’s life and craftsmanship. Philip Reed – White House Historical Association