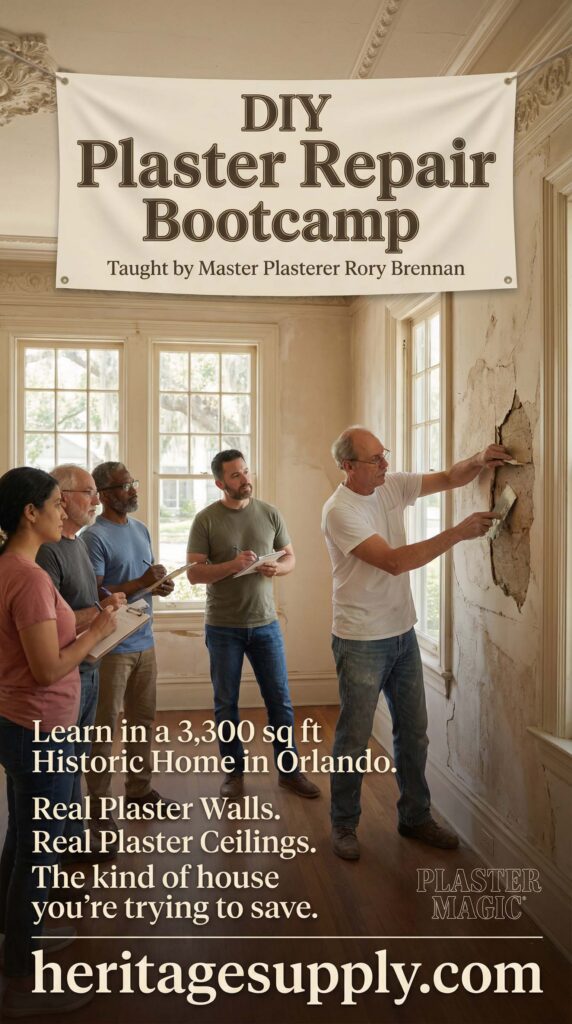

- This event has passed.

Traditional stuccos-historical techniques

March 2, 2023 - March 5, 2023

$1350Overview

This course will introduce us to the exciting world of traditional stucco, in the knowledge of the historical techniques that have accompanied humanity since time immemorial, and will serve as a starting point to delve into them.

Gypsum and lime are simple materials, they come from rocks that are abundant in nature, they require a short manufacturing energy for their implementation.

Great artisans and artists knew how to manipulate them, with a wide variety of techniques, achieving results of great beauty, splendor and efficiency. These techniques contain an immense cultural load, they covered the historical architectures in facades and interiors, providing them with color and complex decorations that enriched them, providing them with effective protection. Thousand-year-old arts were created that accompanied man in his temples, palaces or simple homes, establishing their own languages, such as shouts and whispers that human beings understood. Nothing analogous has ever been achieved with the new materials that are now flooding the market. The absolute forgetfulness of historical techniques and the great artisan massacre have been one of the most negative aspects of the century. The promotion of the new materials that are invading the market, the immense deterrent and convincing power of multinationals that not only put an end to traditional materials, their techniques and craftsmen, but also blinded the professionals, and what is much worse, the official teachings that considered all this as obsolete before the arrival of modernity. But, what has provided the market that can substitute that with advantage? NOTHING. Pericles said: “He who knows and does not explain himself clearly, he is the same as he if he did not think”

Content

- History of stuccos.

- The lime. (History, types of lime, safety, calcined, quenched, aggregates, tools, supports, types of masses, types of finishes).

- Artisan slaking of lime and preparation of lime into paste and lime paste.

- Artisanal and industrial plasters.

- Plaster and lime jobs

- Hydraulized air lime.

- Opus Signimun-Cocciopesto (Roman mortar).

- Tadelakt.

- Ironed on fire.

- Fresh.

- Handmade lime paints.

- Inks, patinas and glazes.

- Treatments and protections (silicates, oils, soaps, nanoparticles, waxes).

- We will create samples in different formats that the student can take with him, working on a table and on a wall with each of the techniques learned.

- Practical application on wall and floor.

TRABADILLOS:

The trabadilIos, mortars prepared with a mixture of

plaster and lime have been used abundantly at all times, at least since the 3rd century after Christ, except in Roman culture, and the hitherto supposed plaster mortars are in many cases small pieces that have survived the action of time. and the environment.

Its performance, its ease and economy of preparation and its durability, increased by empirically and wisely used additives, have allowed us to find these little tricks that have defied the passing of the years today.

plaster and lime have been used abundantly at all times, at least since the 3rd century after Christ, except in Roman culture, and the hitherto supposed plaster mortars are in many cases small pieces that have survived the action of time. and the environment.

Its performance, its ease and economy of preparation and its durability, increased by empirically and wisely used additives, have allowed us to find these little tricks that have defied the passing of the years today.

OPUS SIGNIMUM:

Opus signinum (‘cocciopesto’ in modern Italian) is a building material used in ancient Rome. It is made of tiles shredded into very small pieces, mixed with mortar, and then crushed with a tamper. Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, describes its manufacture: “Even broken pottery has been used; it has been found that, beaten to a powder and tempered with lime, it becomes more solid and durable than other substances of a similar nature; forming the cement known as the “Signine” composition, so widely employed to make even the pavements of houses.” Pliny’s use of the term “Signine” refers to “Signia (modern Segni), the name of a city in Lazio that was famous for its roof tiles.

The technique, probably invented by the Phoenicians, is documented in the early 7th century. B.C. at Tell el-Burak (Lebanon), then in the Phoenician colonies of North Africa, some time before 256 B.C. C., and spread north from there to Sicily and finally to the Italian peninsula. Signinum floors are found extensively in Punic cities in North Africa and commonly in Hellenistic houses in Sicily. While some signinum pavements have been found in Rome, the technique is not common there. Vitruvius describes the process of laying a floor, whether signinum or mosaic. The trend began in the first century BC, proliferating both in private homes and in public buildings. In the second century, the opus signinum would give way to more patterned styles of pavement.

TADELAKT:

Tadelakt is a unique and inimitable lime coating. If we talk about “Tadelakt”, we are talking about a unique lime exclusively from the Marrakech region. The authentic Tadelakt is “only” Tadelakt if the limes come from the Marrakech region due to its extraordinary geological composition, unique in the world, rich in minerals, a high content of limestone from sea shells, and many other compositions and circumstances that are not They occur in other parts of the world.

With this lime, obtained by cooking, a master lime maker (maalem) must prepare the final Tadelakt, with his ancestral knowledge, his secret recipe, passed down from father to son for generations.

All the elaboration of this very special lime is carried out in an artisanal and manual way from the beginning to the end, for generations and generations, from father to son. The art of the app was also jealously guarded by the “Maalems” for generations and remains so to the present day.

In the Arab world, having Tadelakt at home is synonymous with luxury, hygiene, warmth and wealth, just like in the rest of the world today.

In the Arab world, having Tadelakt at home is synonymous with luxury, hygiene, warmth and wealth, just like in the rest of the world today.

FRESCO:

The fresco technique is one in which paint, made up of pigments mixed in water, is spread over a layer of lime mortar that is still wet. Its use dates back to Antiquity and has been used at all times, with little variation in its execution process. It is the fifteenth-century Italian painting treatise writers who established the conditions for creating the “buon fresco”.

The materials used for the execution of this technique are: pure pigments, water and lime mortar. The first two are used for painting itself, while the last one is used to prepare the support.

The mortar used for the fresco is composed of a mixture of lime, aggregates and water. The limestone is heated in a kiln, obtaining quicklime. This lime cannot be used for plastering, and must be extinguished in order to avoid the increase in volume in contact with humidity, which would cause the appearance of cracks and other pathologies. To extinguish, the lime must be submerged in water, after which the theorists required the passage of a long time before its use in paint. So much so, that Michelangelo used for the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, lime that had been dead for thirty years.

On the other hand, the most used aggregates for the execution of a mortar intended for fresco are sand, marble and pozzolan. Marmolina or marble dust was generally used for the last layer of the plaster, since it provided a white, fine and luminous surface. Pozzolan, however, makes it possible to form a hydraulic mortar with very good drying properties that allows it to set even under water.

Fresco painting has been known to various cultures since antiquity, some of which are widely separated geographically. Its stability has allowed us to preserve wonderful examples in a variety of styles.

IRONING ON THE FIRE:

Fire stucco is a variant of the stucco technique that uses a fine-grained paste composed of slaked lime, pulverized marble and natural pigments, which hardens, aided by the heat of a hot iron, by chemical reaction upon contact calcium carbonate from lime with carbon dioxide (CO2)1 and is used above all in finishing walls and ceilings. It is used with advantage, due to its resistance to water, in finishing exterior walls.

Fire stucco admits numerous treatments, among which stand out modeling and sgraffito obtaining ornamental shapes, polishing to give it the appearance of marble or decorating it with polychrome painting.

Schedule:

From 8:30 AM to 6:00 PM with a stop for lunch.

Price:

1,350 dollars per student.

Discounts for groups and couples.

Discounts for groups and couples.